God is the creator and sustainer of all things—and the perfect loving relationship between the Father, Son and Holy Spirit is the foundation of life. Children are created in God’s image, with a capacity for relationships. As educator Charlotte Mason put it, “Education is a science of relations.” Children are whole people and just as children’s bodies need proper nourishment, their minds do as well. Through the use of well- written books, by authors who love their subject, children can meet mind to mind with ideas that are good, right, true, lovely and noble throughout all of academia. Through time spent in nature they can form relationships with God’s creation and through time studying the Bible, children can be led into a relationship with Jesus-- in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge. LS follows Charlotte Mason’s principles of education. By design, the methodology used at LS is not something you will find at a public school, and it is important that as parents and co-educators, you are in complete understanding of the methodology because this will help you understand why we do or do not do certain things. This involves an entire paradigm shift in what education truly is. Instead of worksheets, we focus on excellent literature and narrating it back. Instead of rote memorization, we prioritize learning how to synthesize information and forming relationships with knowledge. Instead of sit down and be quiet, we value hands on learning with varied subjects and facilitate an atmosphere of discussion. Please take some time to learn about the philosophy. We have compiled some resources to help you.

1. ASI video Part 1, Persons or Products? (7:06 minutes) The Ambleside Difference

2. ASI video Part 3, What are We Drawing Students To? (5:41 minutes) The Ambleside Difference

3. Read the book, In Vital Harmony by Karen Glass

5. Listen to New Mason Jar Podcast Episode 11 (Q&A, 42:48)

Below is additional recommended reading:

For the Children’s Sake by Susan Schaeffer Macauley, In Vital Harmony by Karen Glass, Know and Tell by Karen Glass, When Children Love to Learn by Elaine Cooper

and a Charlotte Mason Study Guide by Penny Gardner

The Learning Process used by LifeSchool and described by Charlotte Mason

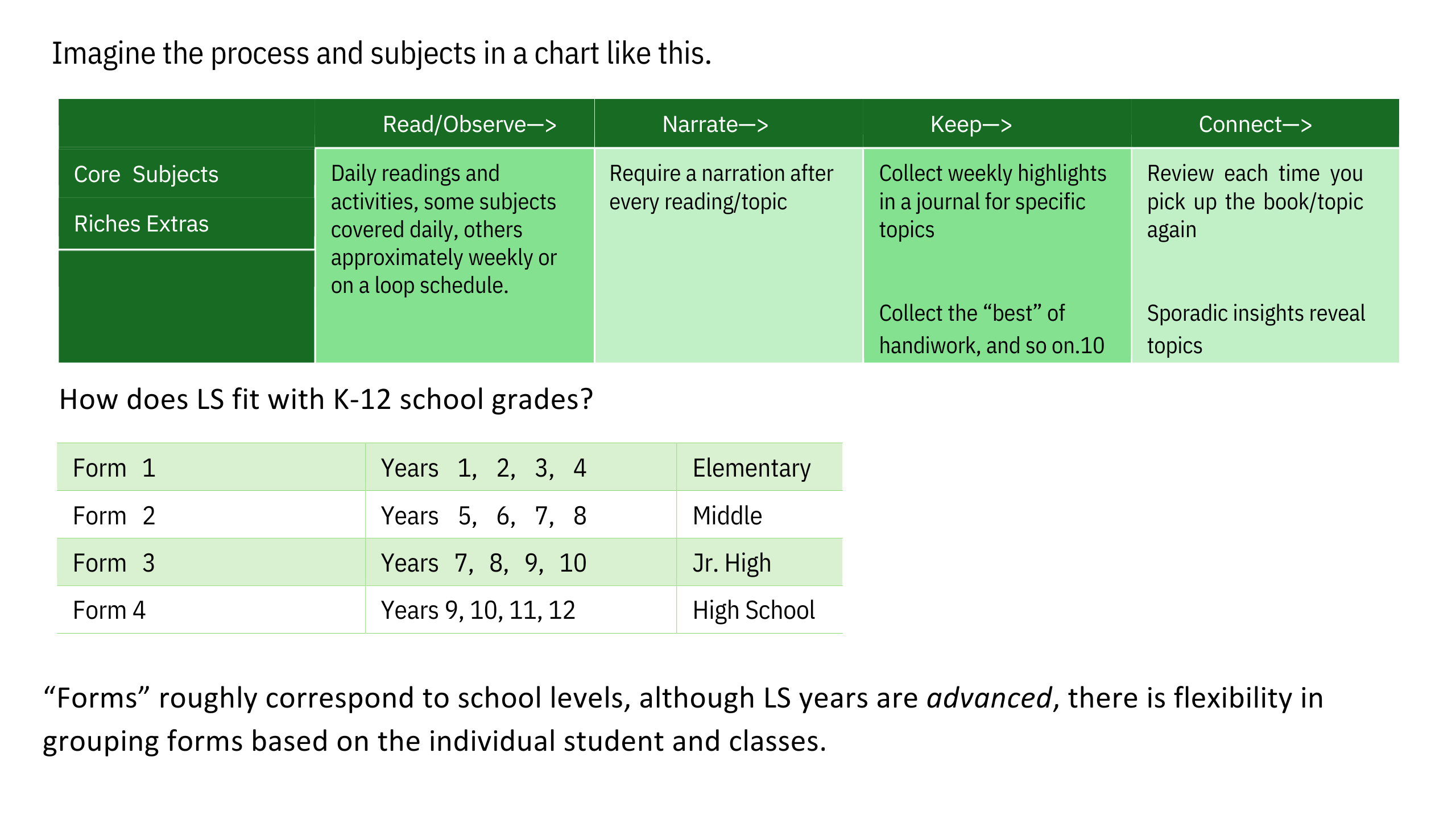

1. Read from “living books” (or Observe, or Notice, such as in nature, art, and music study) with Rapt Attention of the Senses

2. Narrate or Articulate or Recreate or Practice in own words, or actions, or pictures

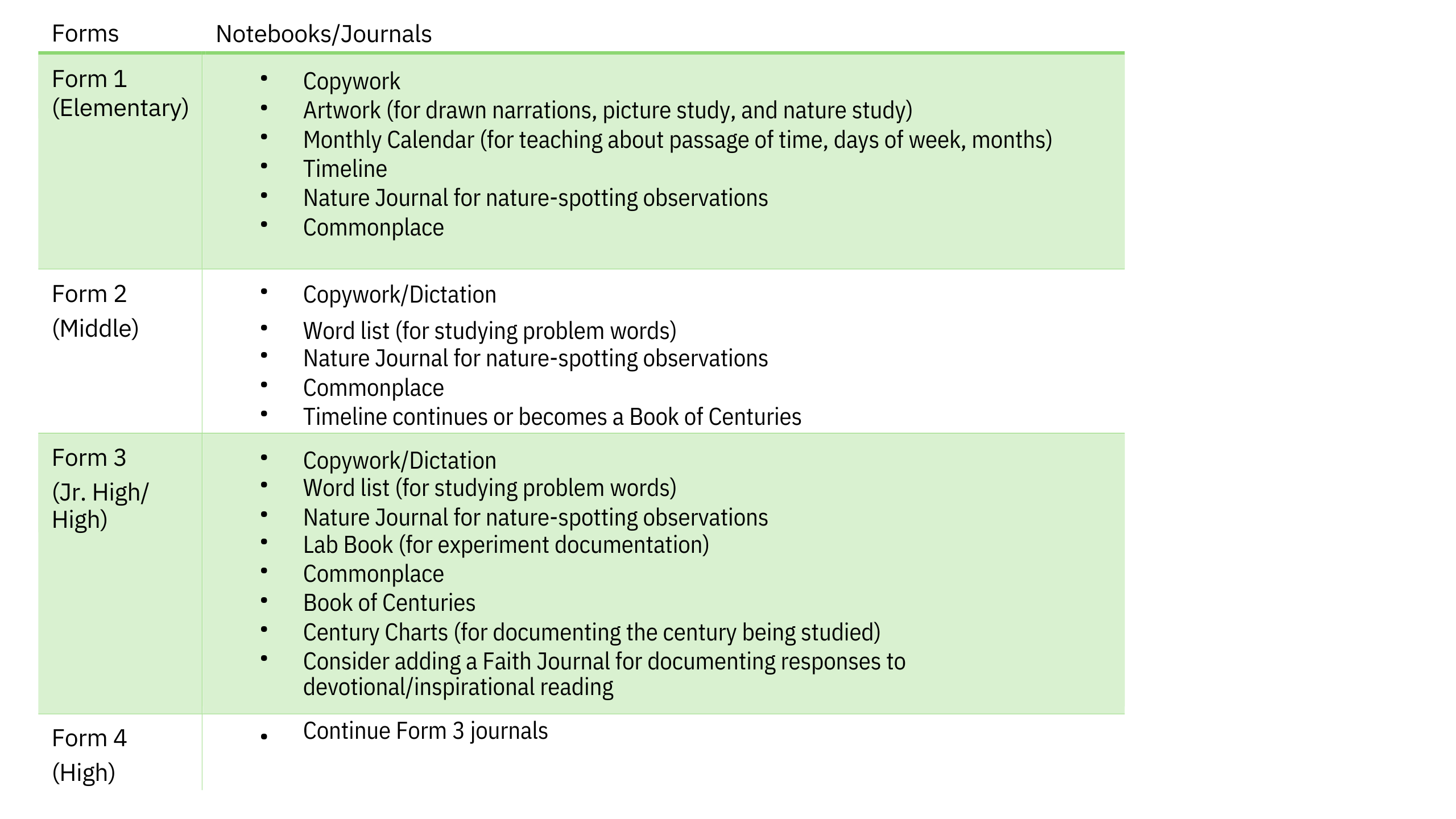

3. Collect and Curate the best bits, like Gems (Keeping in Notebooks, or Timelines, or Journals, or Collections, or Recitations)

4. Connect to other memories/learning (happens sporadically over time)

The first three stages are an intentional part of a LifeSchool (LS) school day; the last is the long-term result that demonstrates—in delightful ways—that the system is working.

This cycle can be applied to any subject, and because all the subjects interconnect and overlap, it works best when it is used for every topic studied.

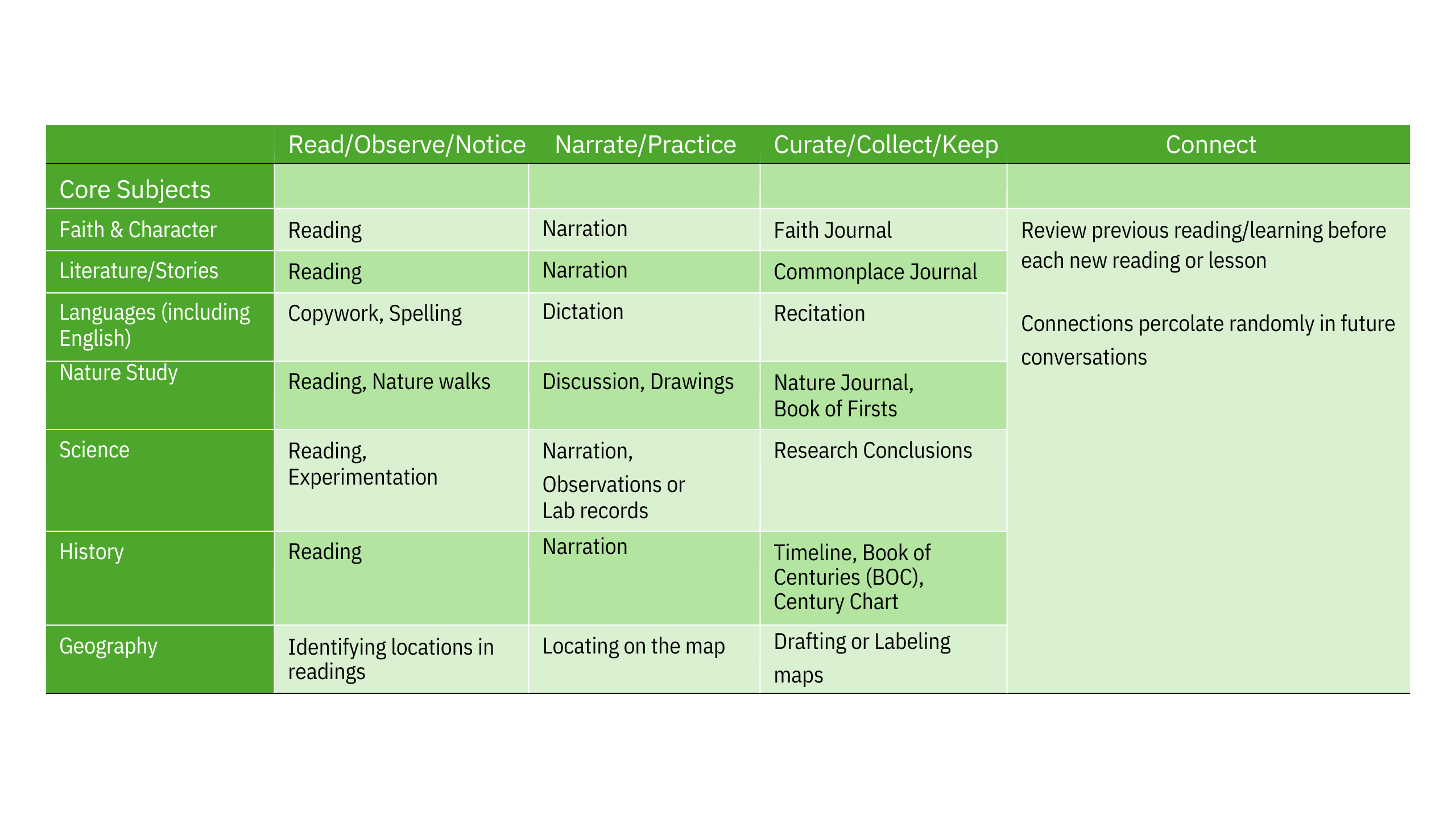

The four stages are applied across all subjects, topics, and experiences:

Read/Observe —> Narrate/Practice —> Collect/Keep/Curate —> Connect

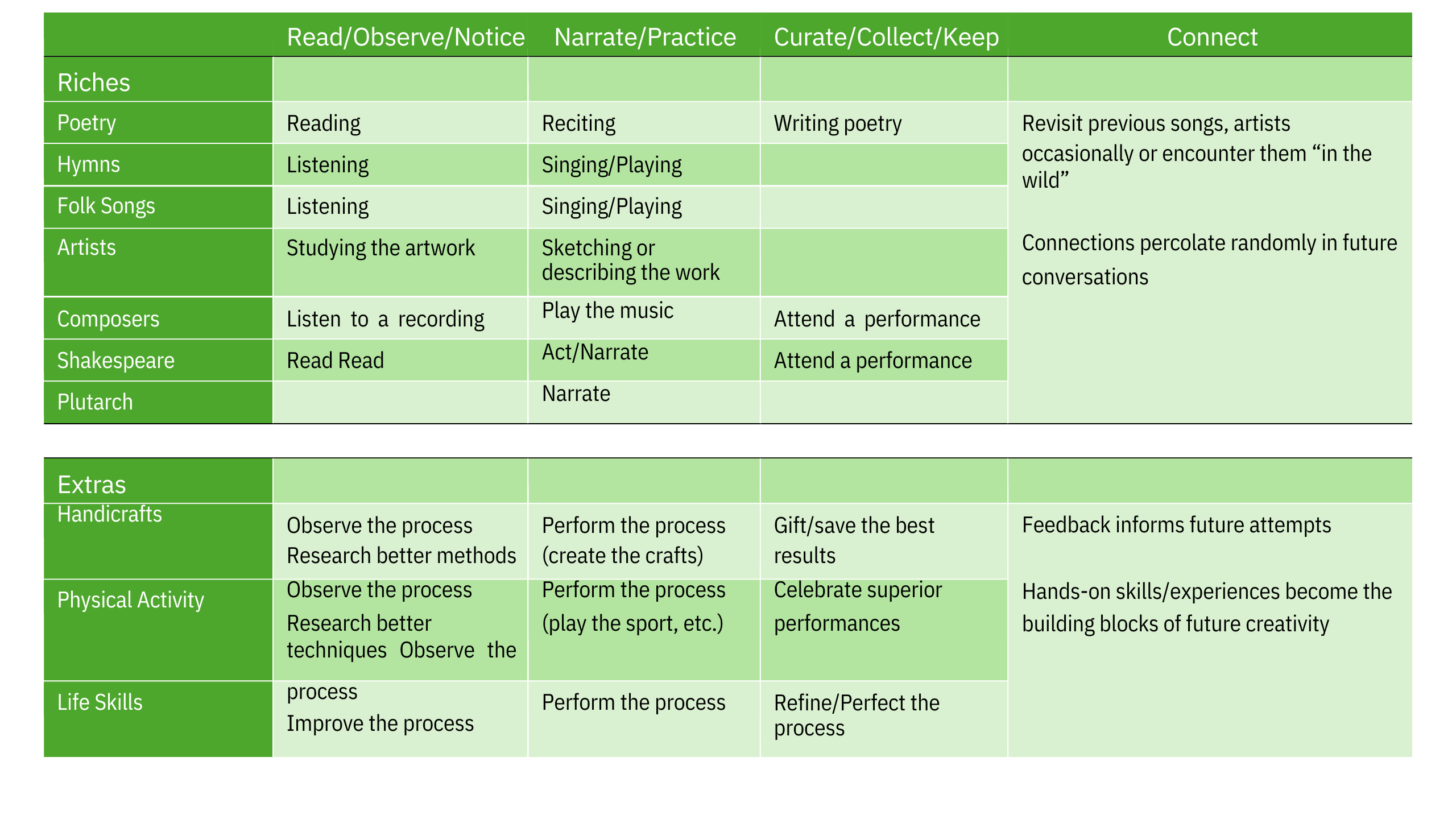

LS’s subjects consist of the following:

• Core Subjects, typically required school subjects, worked individually or in small groups

• Riches, considered enrichment, and worked together.

• Extras, including handiwork, physical activity, life experiences, musical instruments, and foreign languages.

We are putting before our students’ senses as many stories and pictures and sounds and smells and experiences as possible, and coaching them in a flexible method to efficiently process all those experiences. Our goals are that over time—by applying a consistent learning process during their most impressionable years—they are both “learning to learn” and building a lifelong network of interconnected ideas.

How All the Pieces Fit Together

Full attention is expected and a narration is requested after every reading.

In practice, the narration process includes:

1. Reviewing prior material: What happened the last time we read this book?

2. Read the reading. Especially with young children, something quiet for them to do may be provided while they listen, such as drawing or modeling with clay.

3. Ask for narration. This might include “Tell me about the drawing/craft you made while we were reading this story” or “What happened since so-and-so’s father died? Long or detailed readings, are subdivided into smaller portions and asked frequently: “What’s happened so far?”

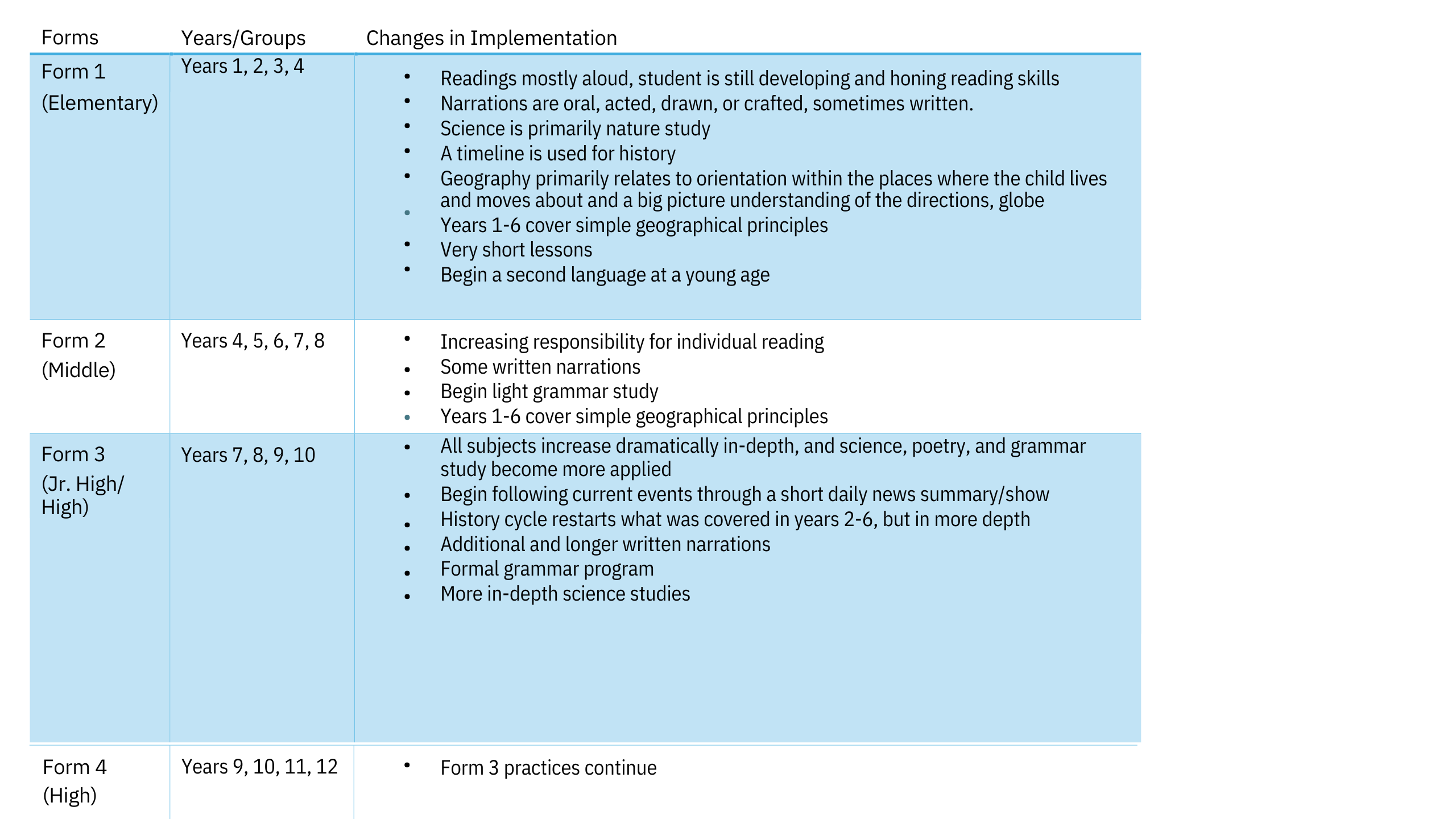

4. Form 2 and up are expected to regularly complete written narrations.

5. Connections are the beautiful light bulb thoughts children articulate at most unexpected moments.

See chart below to place many of these terms within the context of the subject they apply to and the CM cycle stage they occur within.

Implementation Changes As Students Mature

Each Form level represents a significant advancement in reading and writing expectations. The following information is helpful about how the cycle is applied differently as students mature:

This summary would be incomplete without Charlotte Mason’s own summary of her work—her principles—the source of many

oft-quoted phrases. These principles are helpful to remember and satisfying to explore, both by applying them and by reading her six volumes for further illumination.

1. Children are born persons.

2. They are not born either good or bad, but with possibilities for good and for evil.

3. The principles of authority on the one hand, and of obedience on the other, are natural, necessary and fundamental; but––

4. These principles are limited by the respect due to the personality of children, which must not be encroached upon whether by the direct use of fear or love, suggestion or influence, or by undue play upon any one natural desire.

5. Therefore, we are limited to three educational instruments––the atmosphere of environment, the discipline of habit, and the presentation of living ideas. The P.N.E.U. Motto is: “Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, and a life.”

6. When we say that “education is an atmosphere,” we do not mean that a child should be isolated in what may be called a ‘child-environment’ especially adapted and prepared, but that we should take into account the educational value of his natural home atmosphere, both as regards persons and things, and should let him live freely among his proper conditions. It stultifies a child to bring down his world to the child’s’ level.

7. By “education is a discipline,” we mean the discipline of habits, formed definitely and thoughtfully, whether habits of mind or body. Physiologists tell us of the adaptation of brain structures to habitual lines of thought, i.e., to our habits.

8. In saying that “education is a life,” the need of intellectual and moral as well as of physical sustenance is implied. The mind feeds on ideas, and therefore children should have a generous curriculum.

9. We hold that the child’s mind is no mere sac to hold ideas; but is rather, if the figure may be allowed, a spiritual organism, with an appetite for all knowledge. This is its proper diet, with which it is prepared to deal; and which it can digest and assimilate as the body does foodstuffs.

10. Such a doctrine as e.g. the Herbartian, that the mind is a receptacle, lays the stress of education (the preparation of knowledge in enticing morsels duly ordered) upon the teacher. Children taught on this principle are in danger of receiving much teaching with little knowledge; and the teacher’s axiom is,’ what a child learns matters less than how he learns it.”

11. But we, believing that the normal child has powers of mind which fit him to deal with all knowledge proper to him, give him a full and generous curriculum; taking care only that all knowledge offered him is vital, that is, that facts are not presented without their informing ideas. Out of this conception comes our principle that,––

12. “Education is the Science of Relations”; that is, that a child has natural relations with a vast number of things and thoughts: so we train him upon physical exercises, nature lore, handicrafts, science and art, and upon many living books, for we know that our business is not to teach him all about anything, but to help him to make valid as many as may be of–

“Those first-born affinities

“That fit our new existence to existing things.”

13. In devising a SYLLABUS for a normal child, of whatever social class, three points must be considered: (a) He requires much knowledge, for the mind needs sufficient food as much as does the body. (b) The knowledge should be various, for sameness in mental diet does not create appetite (i.e., curiosity) (c) Knowledge should be communicated in well-chosen language, because his attention responds naturally to what is conveyed in literary form.

14. As knowledge is not assimilated until it is reproduced, children should ‘tell back’ after a single reading or hearing: or should write on some part of what they have read.

15. A single reading is insisted on, because children have naturally great power of attention; but this force is dissipated by the re-reading of passages, and also, by questioning, summarising. and the like.

Acting upon these and some other points in the behaviourof mind, we find that the educability of children is enormously greater than has hitherto been supposed, and is but little dependent on such circumstances as heredity and environment.

Nor is the accuracy of this statement limited to clever children or to children of the educated classes: thousands of children in Elementary Schools respond freely to this method, which is based on the behaviour of mind.

16. There are two guides to moral and intellectual self-management to offer to children, which we may call ‘the way of the will’ and ‘the way of the reason.’

17. The way of the will: Children should be taught, (a) to distinguish between ‘I want’ and ‘I will.’ (b) That the way to will effectively is to turn our thoughts from that which we desire but do not will. (c) That the best way to turn our thoughts is to think of or do some quite different thing, entertaining or interesting. (d) That after a little rest in this way, the will returns to its work with new vigour. (This adjunct of the will is familiar to us as diversion, whose office it is to ease us for a time from will effort, that we may ‘will’ again with added power. The use of suggestion as an aid to the will is to be deprecated, as tending to stultify and stereotype character, It would seem that spontaneity is a condition of development, and that human nature needs the discipline of failure as well as of success.)

18. The way of reason: We teach children, too, not to ‘lean (too confidently) to their own understanding’; because the function of reason is to give logical demonstration (a) of mathematical truth, (b) of an initial idea, accepted by the will. In the former case, reason is, practically, an infallible guide, but in the latter, it is not always a safe one; for, whether that idea be right or wrong, reason will confirm it by irrefragable proofs.

19. Therefore, children should be taught, as they become mature enough to understand such teaching, that the chief responsibility which rests on them as persons is the acceptance or rejection of ideas. To help them in this choice we give them principles of conduct, and a wide range of the knowledge fitted to them. These principles should save children from some of the loose thinking and heedless action which cause most of us to live at a lower level than we need.

20. We allow no separation to grow up between the intellectual and ‘spiritual’ life of children, but teach them that the Divine Spirit has constant access to their spirits, and is their Continual Helper in all the interests, duties and joys of life.

“The question is not, -- how much does the youth know when he has finished his education -- but how much does he care? and about how many orders of things does he care? In fact, how large is the room in which he finds his feet set? and, therefore, how full is the life he has before him?”

― Charlotte Mason, School Education

Check us out on Facebook!